Genes Involved in Inflammation, Cellular Structure May Be Therapeutic Targets in Huntington’s

Written by |

Targeting specific genes involved in inflammation and cellular structure may be a therapeutic strategy to reduce protein clumps in patients with Huntington’s disease, according to researchers.

Their study, “High-Throughput Functional Analysis Distinguishes Pathogenic, Nonpathogenic, and Compensatory Transcriptional Changes in Neurodegeneration,” appeared in the journal Cell Systems.

Neurodegenerative disorders affect the activity of many genes across different disease stages. However, differentiating between changes that drive disease from the body’s own compensatory responses still lacks reliable methods.

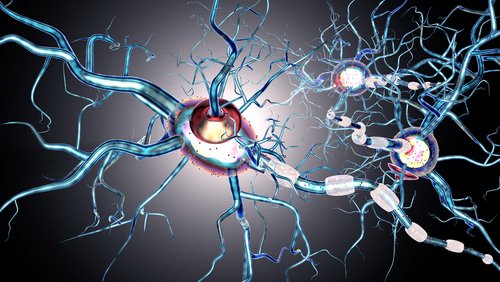

Huntington’s is a representative example of this complexity. Although its cause is well-known and the accumulation of mutant huntingtin (mHTT) protein leads to neuronal loss in relatively limited brain areas, the disorder affects several cellular functions, including inflammation, communication between neurons, DNA repair, clearance of cellular debris, and the intracellular transport of molecules.

At the molecular level, Huntington’s involves changes in thousands of genes, depending on factors such as disease duration and the patient’s genetic background.

To analyze previously reported alterations in gene levels in the brains of Huntington’s patients, researchers at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, developed a high-throughput approach that integrates lab experiments, results from published literature, and analyses of large datasets. They aimed to reveal the functional significance of several molecular changes in a relatively short time.

“Previous studies had been conducted in different mouse models or different patient samples, sometimes with differing results,” Juan Botas, PhD, the study’s senior author, said in a Baylor news story written by Ana Maria Rodrigues, PhD.

“By comparing the genes that were affected repeatedly in different models, we were able to narrow down a set of genes to study from a few thousand to a few hundred,” Botas said.

The scientists first identified 312 genes affected in both early-stage patients and mice with the disorder. They then tested these changes in fruit fly models of Huntington’s, whose neurons exhibit similar HTT clumping as people with the condition.

The flies’ short life spans mean they show symptoms of Huntington’s within a matter of days, rather than months or years as in mammalian models, according to Botas.

“We measured the severity of the flies’ motor impairments in a ‘climbing assay’: tap a test tube with a dozen flies in it, and healthy flies will climb upward,” Botas said. “Flies whose neurons are sick can’t do this test very well.”

The scientists evaluated the effect of the preselected gene changes on disease worsening in the climbing test and on the levels of HTT accumulated inside neurons.

Results showed that while changes in gene expression involved in inflammation or in the cellular cytoskeleton — responsible for cellular structure and motility — were associated with worsening of Huntington’s disease, alterations involved in calcium signaling and neuronal communication were actually counteracting the disease.

The genetic changes that aggravated the disease mediated their effect by increasing the stability of HTT inside neurons, leading to more protein accumulation and toxicity.

Therefore, when scientists reduced the levels of disease-driving genes, they found that mHTT levels were lower, cellular mechanisms to degrade mHTT clumps were activated, and the health of fruit flies was improved.

“We were surprised, in fact, to find that [depletion] of specific inflammation/actin cytoskeleton genes reduced mHTT levels,” they wrote.

“We are encouraged to look for ways to improve the condition by interfering with those proteins to reduce the levels of huntingtin [protein] accumulation and neurotoxicity,” Botas added.

This new approach to studying gene activity could be applied to other neurological diseases, the scientists added.