Huntington’s disease causes

Last updated Aug. 11, 2025, by Marisa Wexler, MS

Huntington’s disease is a neurodegenerative disorder caused by mutations in the HTT gene. This mutation ultimately leads to damage to nerve cells in the brain, resulting in Huntington’s disease symptoms including movement disorders, psychiatric issues, and cognitive problems.

There currently is no Huntington’s disease treatment that can target the disease’s underlying cause, though therapies to help manage symptoms are available.

What causes Huntington’s disease

All cases of Huntington’s are caused by an HTT gene mutation that falls into the category of trinucleotide repeat expansions, where a sequence of three nucleotides (DNA’s building blocks) are excessively repeated. There are no other Huntington’s disease causes.

The HTT gene contains a region where a sequence of three nucleotides — cytosine (C), adenine (A), and guanine (G) — are normally repeated several times. CAG repeat expansions are not stable, and they can progressively lengthen over the course of a person’s lifetime (a process called somatic expansion) and during reproductive processes (particularly when they are transmitted from the father).

The size of the CAG repeat expansion in the HTT gene determines Huntington’s disease risk:

- Twenty-six or fewer repeats are considered normal and are not associated with Huntington’s.

- Twenty-seven to 35 repeats are considered an intermediate expansion. This number of repeats does not cause Huntington’s, but people with an intermediate expansion can have children with Huntington’s.

- Thirty-six to 39 repeats are considered disease-causing, but with reduced penetrance. This means that people with this type of expansion may or may not develop Huntington’s, for reasons that are unclear, and have an increased risk of having children with Huntington’s.

- Forty or more repeats are classified as fully penetrant, meaning it’s virtually guaranteed that people with this number of repeats will have Huntington’s.

Usually, adult-onset Huntington’s is associated with 40 to 50 CAG repeats, while juvenile Huntington’s disease is caused by more than 50 repeats. Moreover, somatic expansions are believed to contribute to disease onset and progression, with a higher number of CAG repeats being closely associated with an earlier age at symptom onset and faster disease progression.

A Huntington’s-causing HTT gene mutation leads to the production of an abnormally long version of the huntingtin protein that is prone to forming toxic clumps in cells.

This particularly affects medium spiny neurons, a type of nerve cell mostly found in a brain region called the striatum that is involved in movement, cognitive function, and emotion. The degeneration and death of these nerve cells ultimately leads to the neurological symptoms that characterize this progressive brain disorder.

While the underlying molecular mechanisms are not fully understood, data suggest that toxic effects of the mutant huntingtin protein as well as healthy huntingtin protein dysfunction may play a role in Huntington’s-associated neurodegeneration.

Inheritance

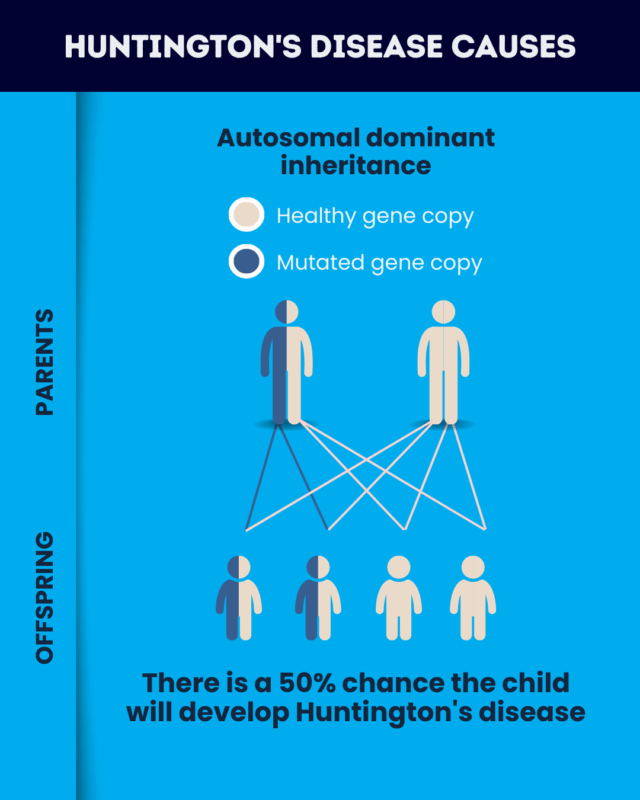

Every person inherits two copies of the HTT gene, one from each biological parent. Huntington’s disease inheritance occurs in an autosomal dominant pattern, meaning that just one copy of the faulty gene is sufficient to cause the condition.

If someone who carries a Huntington’s disease mutation has a biological child, there is a 50% chance that the child will inherit the disease-causing mutation and develop the condition.

Due to CAG repeats’ instability, it is also possible for someone, particularly a man, who carries an intermediate expansion to transmit a Huntington’s-causing mutation to their offspring. Studies estimate that the odds of inheriting a disease-causing mutation in this way range from about 1 in 6,000 to 1 in 1,000.

Risk factors

Family history and the presence of excessive CAG repeats in the HTT gene are the only Huntington’s disease risk factors. People with a family history of Huntington’s are more likely to develop the disorder. In particular, individuals with a biological parent who has Huntington’s have a 50% chance of developing the disease themselves.

Factors affecting progression

Studies have suggested that a range of other factors may affect how the disease manifests, including the age at symptom onset and the speed at which patients progress through Huntington’s stages. These factors may include:

- The number of CAG repeats, with a higher number being associated with earlier age at onset and faster disease progression.

- Gender, as studies indicate that Huntington’s progression is generally faster in women.

- Not smoking and maintaining low-to-moderate alcohol consumption, which are associated with slower disease progression.

- Mental health, as Huntington’s tends to progress faster in patients with a history of mental health problems prior to symptom onset.

- Getting regular exercise, which may help patients maintain functionality for longer.

- Eating a healthy diet, which is important for maintaining overall health. Some studies suggest that certain diet strategies may help slow Huntington’s progression but further research is needed to confirm this.

- Maintaining a more intellectually stimulating and socially engaged lifestyle, which some research suggests is linked to slower Huntington’s progression.

Genetic testing

Genetic testing for Huntington’s can be used to determine the number of CAG repeats in the HTT gene. This can be used to diagnose Huntington’s in people who are already experiencing symptoms or predict whether a person will develop Huntington’s in the future.

It is also possible to perform genetic testing during pregnancy or during the process of certain types of assisted reproductive technology, which can help inform the risk of having a child with Huntington’s.

Although genetic testing is highly accurate, it has some notable limitations, including the inability to accurately predict the risk of Huntington’s in people carrying reduced penetrance mutations.

Also, as there are no treatments to slow or stop Huntington’s progression, individuals deciding whether or not to get tested need to consider how the results might impact their psychological and emotional well-being.

The decision of whether or not to pursue genetic testing for Huntington’s is an extremely personal choice, and each individual should decide what is right for them.

Huntington’s Disease News is strictly a news and information website about the disease. It does not provide medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. This content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website.

Recent Posts

- The challenges of navigating dating while living with Huntington’s disease

- Guest Voice: I hate Huntington’s disease, but I love my husband

- New Zealand OKs Phase 1 trial of Huntington’s therapy SRP-1005

- Nothing compares to a punny Valentine’s Day play

- It’s OK to reach out for help during the February slump

- Huntington’s treatment safely slows disease over 9 months in early trial

- A new puppy gives my gene-positive wife a sense of purpose

- Toward a better understanding of anger as a symptom of Huntington’s disease

- Actor Will Forte shares family story in Teva awareness campaign

- Finding ‘space in the middle’ to deal with life’s challenges