NfL Protein Levels Linked to Brain Damage in Huntington’s Children

Levels of neurofilament light chain, a marker of nerve cell degeneration, are increased in children with juvenile-onset Huntington’s disease (JOHD), according to a new study.

Results also suggest that levels of this protein, known as NfL, are correlated in these young patients both with disease severity and damage to brain regions affected by Huntington’s.

The researchers note that assessing NfL levels could help clinicians to better diagnose children with juvenile-onset Huntington’s — and aid in predicting symptom development in young patients with the hereditary disease.

The study, “Neurofilament Light Protein as a Potential Blood Biomarker for Huntington’s Disease in Children,” was published in Movement Disorders.

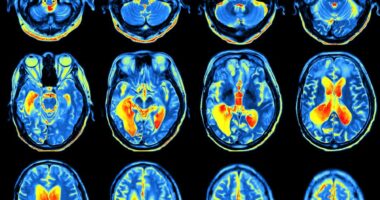

Huntington’s is caused by mutations in the HTT gene, which result in nerve cell degeneration. The nerves in a brain region called the striatum, which is involved in voluntary movement, among other body functions, are usually the most severely affected.

Neurofilament light chain, or NfL, is a structural protein in nerve cells (neurons). When these cells are damaged, NfL is released into the body, and can be detected in plasma — the non-cell part of blood — and other bodily fluids.

Prior research has shown that plasma NfL levels can serve as a marker of disease progression in adults with Huntington’s disease. However, its utility in children with Huntington’s has not been thoroughly studied.

To learn more, a team of scientists in the U.S. and the U.K. conducted an analysis of data from two observational studies.

Nine children with JOHD, as well as 30 children with pre-manifest Huntington’s — meaning they had a known genetic mutation expected to cause Huntington’s later in life, but had not yet begun experiencing symptoms — were included in the analysis. The JOHD patients had a mean age of 16, while the mean age of those with preHD was 14. The analysis also included 61 people with no Huntington’s-associated mutations, who served as controls.

The average plasma NfL levels in the controls and preHD patients were similar — about 5.5 picograms per milliliter (pg/mL) in both groups. Average NfL levels in children with JOHD were about seven times higher, or just over 30 pg/mL. Analyses revealed that a cutoff of 9.64 pg/mL could accurately classify 91% of JOHD patients and 96% of controls.

“The substantial increases in plasma NfL levels observed in JOHD participants could … assist clinicians in providing a timely diagnosis to patients with JOHD,” the researchers wrote, adding that the “plasma NfL levels could provide additional information for practitioners struggling to decide if confirmatory genetic testing is warranted in a minor when a clinical diagnosis of JOHD is not clear.”

The team also noted that NfL levels may be a useful “much-needed” outcome measurement to use in clinical trials that are investigating potential treatments for Huntington’s.

For the preHD children, analyses of their specific mutations were used to predict how many years it would be before they would likely start developing symptoms.

Among these patients, plasma NfL levels did not significantly differ from the controls for children who were predicted to develop symptoms at the age of 20 or older. However, plasma NfL levels were significantly increased in those predicted to develop symptoms before age 20.

A cutoff value of 19.09 pg/mL could accurately classify 82% of children with JOHD and 100% of those with preHD, analyses showed. The scientists proposed that tracking NfL levels could help inform decisions about when to start treatment for patients with preHD.

Further analyses of the children with elevated NfL levels — those with JOHD or who were within two decades of disease onset — revealed that higher plasma NfL levels were significantly associated with a greater reduction in the size of the striatum. The researchers noted that detecting striatum changes in children with juvenile-onset Huntington’s is often complicated because this brain region usually shrinks somewhat in normal development over the course of childhood and adolescence regardless of disease.

“Plasma NfL levels could … help distinguish between neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative processes,” the scientists wrote.

A separate analysis that also included data for people with adult-onset Huntington’s suggested that higher NfL levels also are correlated with more severe disease burden scores. These results show that NfL is a potential biomarker for Hungtinton’s, the scientists said.