German Researcher Promotes Non-drug Alternatives for Treating Huntington’s

Written by |

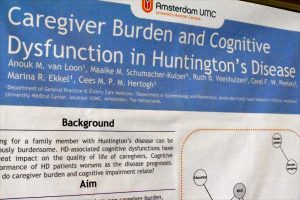

Herwig Lange, MD, has been researching Huntington's disease since 1969. He spoke Feb. 14 at ECCH in Vienna on non-drug approaches to treating Huntington's. (Photos by Larry Luxner)

At least three major pharmaceutical companies are looking into potential gene therapies for Huntington’s disease — a rare inherited condition without a cure or a treatment to stop its progression.

While several approved therapies exist to control the disorder’s physical and psychiatric effects, non-drug alternatives to alleviate the worst symptoms of Huntington’s shouldn’t be overlooked, says a top expert on the subject.

“Many doctors say there’s nothing we can do for people with Huntington’s, but that’s totally wrong,” said German neurologist Herwig Lange, MD, who founded his country’s first Huntington’s disease clinic in Düsseldorf in 1982. “There’s a lot you can do to improve their quality of life now.”

He added: “Even neurologists know little about [Huntington’s disease]. They don’t recognize the psychiatric and cognitive issues. That’s why it takes eight years to arrive at a diagnosis.

Lange was among several experts who spoke at the European Conference on Controversies in Huntington’s Disease (ECCH2020), held Feb. 13–14 in Vienna.

Scientists have observed a huge variation in the age of onset of Huntington’s, Lange said, often plus or minus 25 years, even among twins. That’s because of the high correlation between the age of onset and the number of repeats of a portion of DNA called CAG trinucleotide repeats within the huntingtin gene.

Healthy people usually have up to 36 CAG repeats; those with more than 36 develop the disease. Research shows that the length of inherited CAG repeats in that gene determines the age at which motor symptoms appear, with longer repeat expansions leading to earlier onset.

But that accounts for only half the variation. Other factors explain the rest, Lange said. For example, studies link higher temperatures with earlier Huntington’s onset. There’s also evidence showing that the disease progresses more slowly in heavier people. In addition, men tend to experience slower disease progression than women — especially men who inherit Huntington’s from their mothers.

A sedentary lifestyle may be a preclinical expression of Huntington’s, and contributes to the earlier onset of symptoms. Overcoming the tendency to be inactive may substantially delay onset of the disease, Lange suggested.

Since there’s no cure for Huntington’s, he recommends that people with the disorder stay moderately active doing something they enjoy.

“The brain has to do something. Understimulation — or overstimulation — will kill the brain cells,” he said. “A healthy diet is also important, and if you ruin your brain cells with alcohol, you will lose a lifetime. Smoking also kills brain cells. The incidence of strokes is 12 times higher among people who smoke.”

This is relevant, Lange said, because 25% of his Huntington’s patients are addicted to drugs, nicotine, or alcohol.

Even coffee may be a problem. Caffeine consumption greater than 190 mg a day — the equivalent of two small cups of regular coffee — has been linked to earlier onset of Huntington’s by an average 3.6 years.

“In my lifetime, I’ve seen about 4,000 Huntington’s patients, and one-fourth have substance abuse problems,” said Lange, who did his doctoral thesis in 1969 on how the disease changes the brain. “They weigh less because they have problems getting food to their mouths, and also because of swallowing difficulties. But if they start with good body weight, their prognosis is better.”

Several approved therapies are on the market to treat the muscle contractions, jerky involuntary movements, and psychiatric problems associated with the disease.

“In addition, Roche, Novartis, and Pfizer are all working on gene therapies for Huntington’s. They all failed with Alzheimer’s, and now they’re hoping for a $2.2-million drug for [Huntington’s disease],” Lange said, referencing the approximate price for Zolgensma — a one-time gene therapy for spinal muscular atrophy that was developed by Novartis. “That’s what they’re aiming at, but no medical system can pay for that. Only a few people will get it, so it’s not a solution for the majority of the [Huntington’s disease] community.”

Huntington’s patients in South America would be excluded from such a gene therapy, Lange said, since it would be way beyond the budget of their governments to afford it.

The United States is home to about 80,000 people with Huntington’s. Europe has about 240,000, and the mutation is present in 140 per 100,000 Europeans, Lange said.

For Huntington’s patients, falls are a big problem, with 25% of recurring falls involving obstacles on the floor, another 20% while using stairs, and 18% happening on uneven or slippery floors. In addition, 93% of falls take place in a familiar environment, and 58% of them are indoors.

Lange said that he cannot overestimate the importance of a happy and healthy lifestyle for people with the disease. This means maintaining a healthy body weight, doing moderate physical and mental activity, getting enough sleep, reducing stress, and using relaxation techniques and psychotherapy — as often and as much as the patient is willing to do.

“Having a social network is also essential,” he added. “I started my clinical career caring just as much about the families as the patient. If the principal caregiver goes down, the next day the patient goes down as well.”