Molecule Shows Potential to Protect Neurons in Early Huntington’s Disease Study

Written by |

A research report discusses the use of six versions of a new type of molecule, known as xyloketal B, for the treatment of Huntington’s disease. Scientists tested the six possible drugs in a worm model of Huntington’s disease, Caenorhabditis elegans. Results of the study, “Xyloketal-derived small molecules show protective effect by decreasing mutant Huntingtin protein aggregates inCaenorhabditis elegans model of Huntington’s disease,“ were published in the journal Drug Design, Development and Therapy.

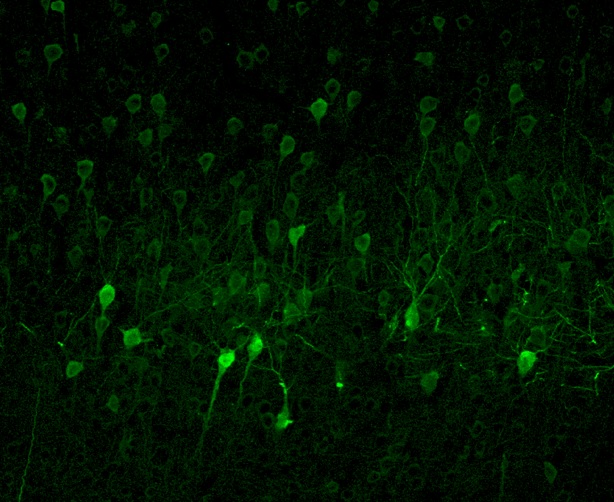

In Huntington’s, the loss of brain cell connections occurs in regions that process movement, called the basal ganglia and cortex, in early phases of the disease. These lost connections inhibit other neurons that process movement, leading to symptoms like jerky movement and involuntary twitching. Understanding how to block neuron death and the excitability of specific nerve cell connections may lead to new therapies.

Xyloketal B is a molecule that naturally occurs in the mangrove fungus. Research in animal models of Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease has shown the molecule has neuron-protective effects, suggesting it might be a treatment for the neuronal death that occurs in Huntington’s disease.

The team, led by Yixuan Zeng of the Department of Neurology, Sun Yat-sen University, in Guangdong, China, created six different versions of xyloketal B, and looked at its ability to protect neurons in a Huntington’s disease model. Worms used in the model worms are genetically modified to produce mutant Huntingtin (Htt) protein — the same protein found in humans with the disease.

Researchers discovered that all six forms of xyloketal B compounds protected neurons from Htt protein-induced death, likely by preventing the protein from clumping together in a process known as aggregation.

“Xyloketal derivatives could be novel drug candidates for treating Huntington’s disease. Further, protective candidate drugs could be designed in future using the guidance of molecular docking results,” the researchers wrote. Extensive research, however, is necessary before these molecules could advance into human clinical trials.

Currently, Huntington’s disease has no cure and no effective treatments that delay disease progression.