Transplants of Healthy Glial Cell Seen to Prevent Huntington Symptoms in Mice

Written by |

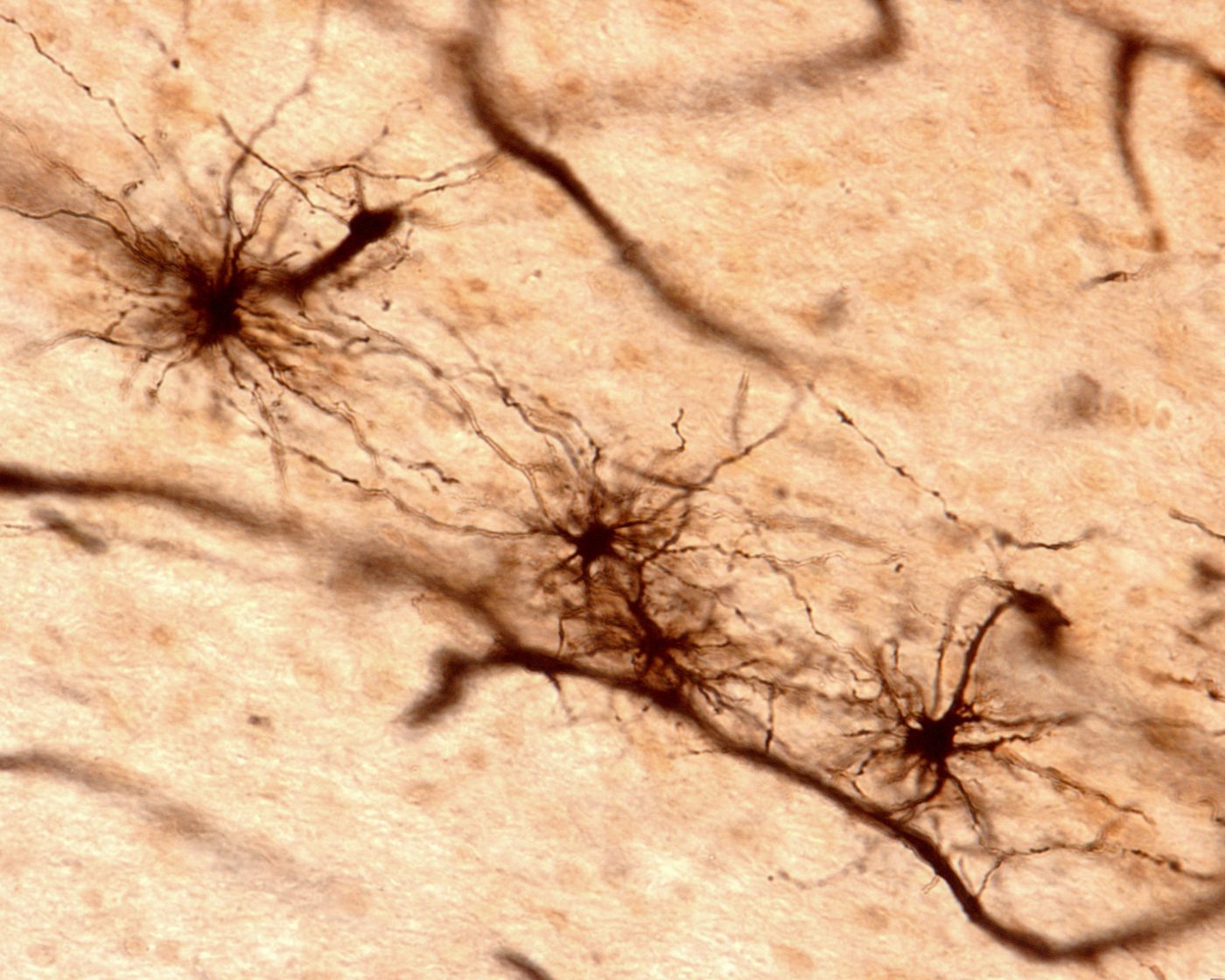

Groundbreaking research from the University of Copenhagen showed that healthy glial cells, transplanted into the brains of mice in a Huntington’s disease model, improved symptoms and prolonged the animals’ lives, demonstrating that glial cells actively contribute to disease processes — a finding with potentially far-reaching implications for the research into, and treatment of, neurodegenerative diseases.

Recently acquired knowledge shows that glial cells in the brain actively contribute to the function of neurons, and Huntington studies have indicated that not only neurons, but also glia, seem to be dysfunctional. Despite this, studies focusing on a glial contribution to Huntington’s or other neurological diseases are few.

“It’s the first time we’ve conducted this type of transplant, and the results are both positive and surprising. It reveals that diseased mice injected with healthy glial cells live longer, and their condition improves. This is very promising, and it’s only the tip of the iceberg. We hope to be able to conduct further research on whether this method could possibly result in a treatment for Huntington’s,” Professor Steven Goldman, the study’s senior author, said in a news release.

The study, “Human glia can both induce and rescue aspects of disease phenotype in Huntington disease,” did not start with this finding. Instead, researchers performed the reverse experiment — they transplanted precursors of human glial cells holding the Huntingtin mutation into the brains of healthy newborn mice. Tracing the spread of these newly introduced glial cells, the team could see that the cells multiplied and spread in mice brains. And as these mice came into adulthood, they developed Huntington-like motor symptoms.

To the researchers, which included collaborators at the University of Rochester in New York, this was a clear sign that glia could drive Huntington’s disease processes, and so, they went on with the second experiment — transplanting healthy human glia into mice with the Huntingtin mutation. The effect was equally clear. Findings, published in the journal Nature Communications, show that these animals had better motor skills and cognitive abilities than their non-treated mates. They also lived longer.

“This is at least in part due to the fact that glial cells control the level of potassium in the brain, which is vital for our motor and cognitive skills,” said Dr. Goldman. “In Huntington disease, the level of potassium in brain tissue becomes unstable, but when the glia cells are injected they restore potassium to normal levels. We hope that as we continue our research on these mechanisms in the future, that it will bring us closer to finding a meaningful treatment for Huntington’s, and possibly other similar neurodegenerative diseases.”

The study has its limitations. The transplants were made in newborn mice, so the question remains whether transplanting healthy glia to mice already showing signs of the disease would be equally beneficial. The research team is already exploring this possibility, and should it succeed, clinical trials could be the next step.