Single Injection Silenced Huntington’s Gene Activity for 6 Months in Mice

Written by |

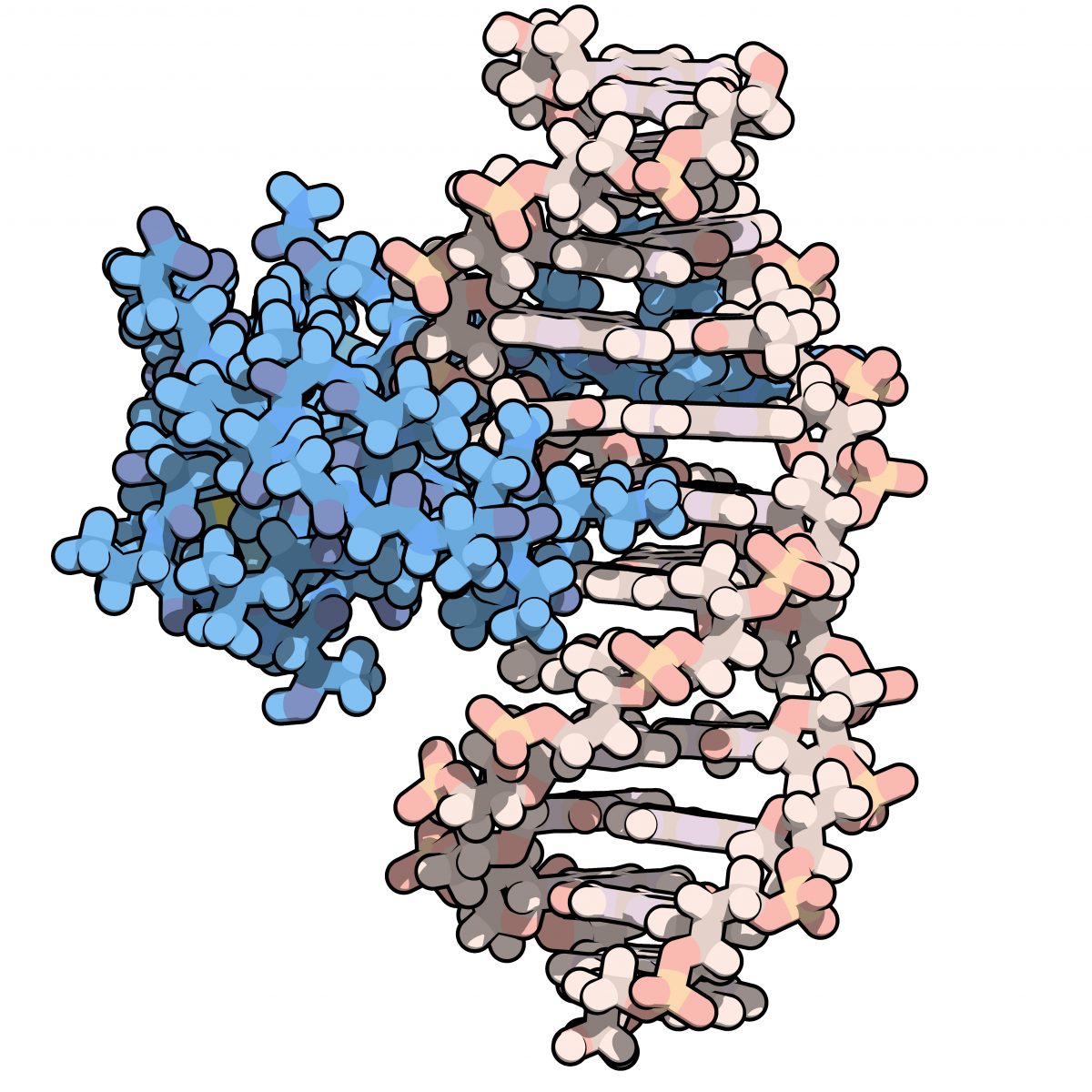

Depiction of zinc finger bound to DNA.

Attempts to block the activity of the mutant huntingtin gene, which causes Huntington’s disease, may have taken a big step forward. Scientists report they successfully silenced the gene for six months after a single injection in a mouse model of the disease.

The study, “Deimmunization for gene therapy: host matching of synthetic zinc finger constructs enables long-term mutant Huntingtin repression in mice,” was published in the journal Molecular Neurodegeneration. Researchers used an engineered protein with the curious name “zinc finger” to turn the gene off, and showed that injecting the protein into the brains of mice did not give rise to unacceptable side effects.

Since piling up of the mutant huntingtin protein is what somehow causes neurons to die, the idea of completely turning off the mutant gene has been explored for some time. But the task has many difficulties and it has taken researchers a long time to succeed. The research team at Imperial College London now hopes the treatment will be ready for human clinical trials in about five years.

Among other molecular duties, zinc fingers — the proteins that got their name because they contain zinc ions and resemble a finger — bind to DNA to control the activity of genes. Researchers have been eyeing this protein group for some time as a potential Huntington’s treatment.

Introducing a new protein into the variety of the cells in the brain is also not an easy task. It gets even more complicated by the fact that Huntington’s patients carry both a mutated and a healthy gene copy, so researchers need to find a way to turn off only the mutant copy.

Researchers at the EU-funded project FINGERS4CURE, who were able to silence the gene in Huntington’s mice for six months, had previously blocked the activity of the gene for only a few weeks. In earlier experiments, introduction of the protein into the brain was also linked to immune reactions, causing additional nerve cells to die.

By changing the composition of the zinc finger, among other adaptations made so that it mimicked a natural mouse protein, researchers succeeded in extending the silencing of the huntingtin gene as well as avoiding immune-related side effects.

The team injected the protein — carried by non-infectious viral vectors — into fluid-filled cavities known as ventricles in the brain. Three weeks later, they saw that the drug repressed up to 77 percent of mutant huntingtin production throughout the brain. After 12 weeks, the treatment still silenced 48 percent of the gene activity, and at six months, the number was 23 percent, a level of repression researchers believe is enough to reduce symptoms.

“While these encouraging results in mice mean that the zinc finger looks like a good candidate to take forward to human trials, we still need to do a lot of work first to answer important questions around the safety of the intervention,” Mark Isalan, from the Department of Life Sciences at Imperial College London and the study’s senior author, said in a news release.

Among the issues researchers now need to investigate is whether the treatment is still effective after repeated injections, whether its effectiveness can be extended for longer periods, and if repeated treatment might be linked to long-term side effects.

“In this study we weren’t looking at how repressing the gene activity affected the symptoms of the disease, and this is obviously a critical question as well. However, we have reason to be confident from our previous studies that repressing the gene does in fact significantly reduce symptoms,” Isalan said.