Mitochondrial Energy Processes in Huntington’s May Be Normal After All

Written by |

Mitochondrial abnormalities may not contribute to the degeneration of neurons in the striatum in patients with Huntington’s disease, according to a study that provides evidence contradicting several earlier findings.

The study explored mitochondrial processes in a mouse model of Huntington’s disease and found that mitochondria from the striatum — the brain region mainly affected in Huntington’s disease — were no different than those from normal mice.

The study, “Oxidative metabolism and Ca2+ handling in striatal mitochondria from YAC128 mice, a model of Huntington’s disease,” was published in the journal Neurochemistry International.

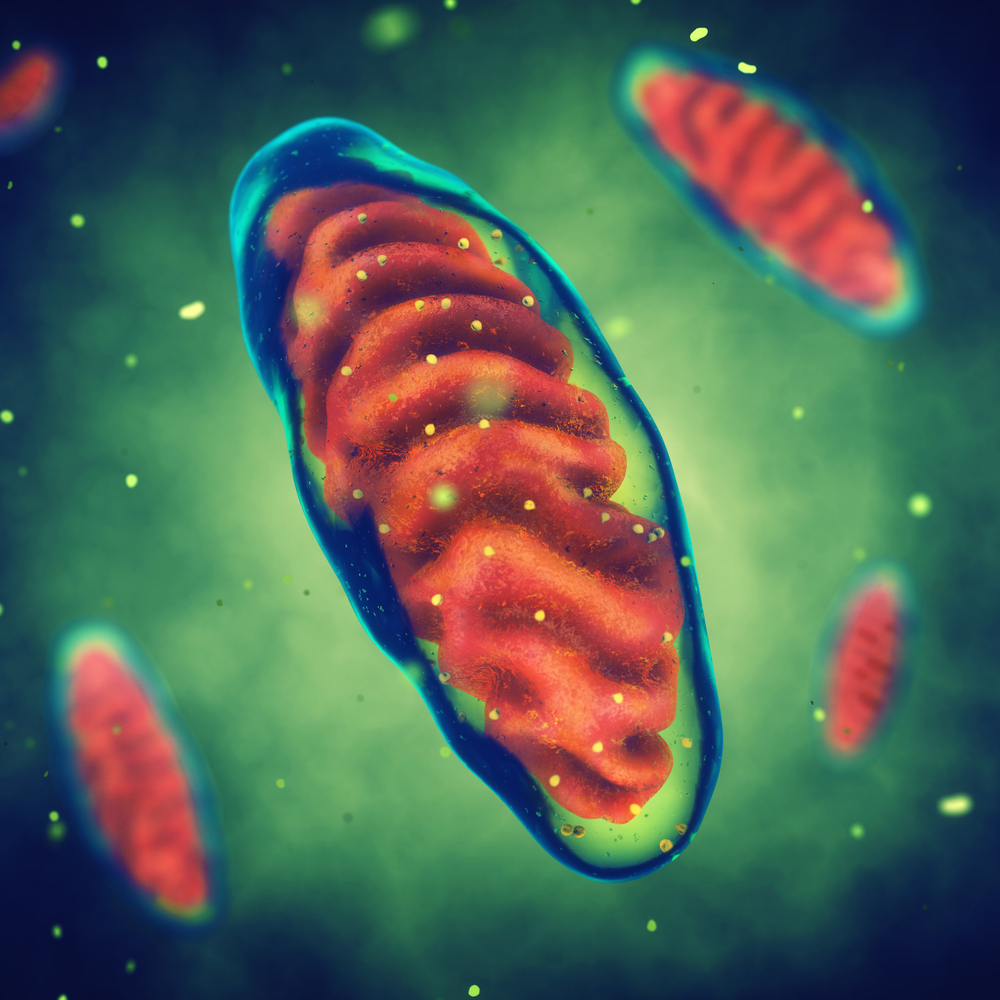

Researchers are still on the lookout for the mechanisms that cause neurodegeneration in patients with a mutated huntingtin gene, and several earlier studies have suggested that abnormal energy production by mitochondria — the cell parts that convert nutrients to energy — may contribute to cell death.

Mitochondria use calcium as a major means of communication with other cell structures, and earlier studies have also shown that Huntington’s-affected mitochondria altered calcium signaling processes.

But researchers at Indiana University School of Medicine show evidence that there is nothing wrong with the mitochondria. In earlier studies, the research team showed there was nothing wrong with mitochondria isolated from the whole brain of two different Huntington’s mouse models.

In the new study, they focused only on the striatum, as this is the brain region in which most damage occurs. They isolated mitochondria from both synapses and other locations from 2-month-old mice. This is an age where the mice start showing mild symptoms.

But examining the respiratory rate and the ability of the mitochondria to take up calcium, they found no differences between normal and Huntington’s mice. The team also analyzed the levels of several mitochondrial proteins, and again found no difference between healthy and diseased mice.

While several studies have found evidence suggesting that the energy production in mitochondria is flawed in Huntington’s, the Indiana researchers aren’t the only ones finding evidence to the contrary.

The majority of the studies investigated mice or lab-grown cells, but the Indiana team said that a study in human patients, in which mitochondrial activity was measured with a brain imaging technique, also failed to find abnormal energy processes in mitochondria.