Scientists Use Fat Bubbles to Deliver Treatments Directly to Brain

Written by |

Researchers have developed a new way to deliver therapies to areas of the brain they have been unable to reach due to the blood-brain barrier that protects the brain from microorganisms.

The technique may lead to new treatments of neurological disorders, including Huntington’s disease, according to the research.

The study, “Lipid Microbubbles As A Vehicle For Targeted Drug Delivery Using Focused Ultrasound-Induced Blood-Brain Barrier Opening,” was published in the Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism.

Scientists have had enormous difficulty delivering therapies to specific areas of the brain due to the blood-brain barrier. The membrane prevents pathogens in the blood from entering the brain but also blocks neurological therapies. Pathogens include viruses, bacteria and fungi.

A team led by Elisa Konogafou has developed a novel way to get brain therapies through the blood-brain barrier.

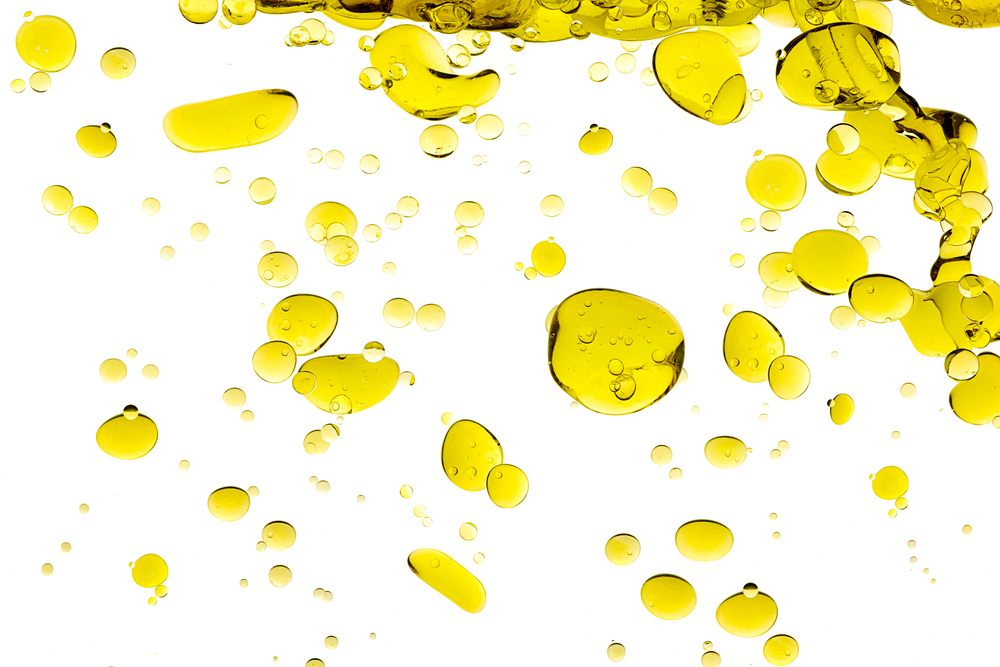

The method consists of embedding therapies in small bubbles of fat, injecting the bubbles into the bloodstream, then using ultrasound to oscillate the bubbles to make them larger. When the bubbles increase to eight microns, they are able to get past the blood-brain barrier so they can deliver the treatments to the brain.

“We’ve made a step forward by incorporating the substance we’re interested in into the lipid (fatty-acid) coating of the microbubbles,” Carlos Sierra, the study’s first author, said in a news release. “This makes the substance stay adhered to the microbubbles and prevents it circulating freely through the body.”

An injection sends the treatment to all parts of the body, but ultrasound allows its release only in the desired area of the brain, so the rest of the body remains unaffected. “It does all this, while being non-invasive, reversible and completely safe,” Sierra added.

The researchers have tested the technique in mice. They used a fluorescent dye to track the location of the microbubbles under a microscope to make sure they were delivered to the desired brain area. The study also identified the level of ultrasound frequency needed for the therapy to reach its target.

The team believes that, if the technique shows promising results in more complex animals, such as monkeys, it can be tested in humans with neurological diseases, such as Huntington’s, Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s, and also patients with brain tumors and strokes. They expect the technique to help design better treatments and reduce side effects.

The researchers have begun testing the technique for delivering therapy to Parkinson’s patients. Preliminary results have been promising.

“[T]he success of this technique in mice, and even in monkeys, can’t guarantee it will be effective in people, but if we continue to get satisfactory results then pre-clinical trials on humans would begin,” Sierra said.