Faulty cellular waste disposal system may drive Huntington’s: Study

Mutant protein behind disease seen disrupting quality

Written by |

Disruption of lysosomal quality control — a system that keeps lysosomes, the cell’s waste-disposal units, working properly — may contribute to the development of Huntington’s disease, according to a study in cell and mouse models of the disease.

Lysosomal quality control, or LQC, typically helps nerve cells repair or replace damaged lysosomes, allowing them to safely break down unwanted proteins and maintain their health.

A team of researchers in Italy found that the mutant huntingtin (muHTT) protein that drives Huntington’s interferes with this system by trapping two key proteins, TFEB and TFE3. This reduces their activity, resulting in an impaired ability to clear damaged lysosomes that may increase susceptibility to muHTT clumps.

“Our experiments suggest that LQC impairment might contribute to [Huntington’s disease],” the researchers wrote.

The study, “Impairment of lysosomal quality control in Huntington disease,” was published in Cell Death and Disease.

Quality control

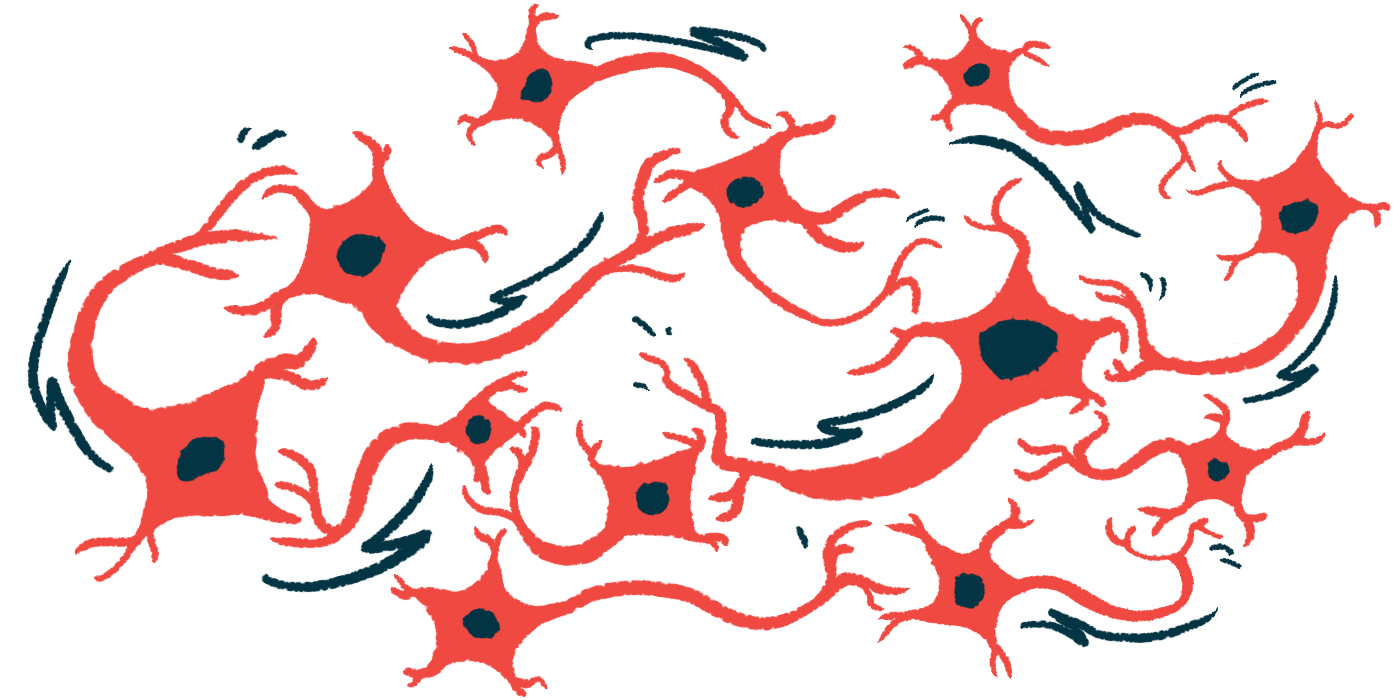

Huntington’s is caused by mutations in the HTT gene that lead to the production of muHTT. This abnormal protein misfolds and accumulates inside nerve cells, forming toxic clumps that trap essential proteins, disrupt normal cellular functions, and ultimately contribute to Huntington’s symptoms.

Under normal conditions, cells rely on lysosomes to clear damaged or abnormal proteins through a process called autophagy. When lysosomes are damaged, this cleanup system breaks down, allowing toxic material to build up inside cells.

To keep lysosomes healthy, cells use a system known as lysosomal quality control. This system relies on a protein called galectin-3 (LGALS3) to detect and flag damaged lysosomes for repair or removal (lysophagy).

“In the presence of lysosomal deficiency due to less efficient repair and/or lysophagy, a compensatory mechanism triggers the activation of transcription factors EB and E3 (TFEB and TFE3),” which promote regeneration through the formation of new lysosomes, the researchers wrote. Transcription factors are proteins that regulate gene activity by binding to specific DNA sequences.

Previous studies have shown that autophagy is impaired and TFEB activity is reduced in Huntington’s, and that LGALS3 levels are elevated in the brains and blood of Huntington’s patients and mouse models.

The team set out to further investigate the role of TFEB, TFE3, and lysosomal damage in Huntington’s development.

They first examined where TFEB and TFE3 are located in brain tissue from a Huntington’s mouse model and in lab-grown cells of the mouse striatum engineered to produce two forms of muHTT: one with a shorter abnormal section that forms fewer clumps, and another with a longer abnormal section that makes the protein more prone to clump together.

The striatum is a brain region critical for motor control, emotion, and cognition that is significantly affected in Huntington’s.

In cell and mouse models, TFEB and TFE3 were found to be abnormally trapped within toxic muHTT clumps, rather than exhibiting the spread-out distribution typically seen in the presence of normal huntingtin protein. In mice’s brains, this sequestration was observed in nerve cells of the striatum and cortex, another brain region known to be affected in Huntington’s.

In lab-grown striatal cells, TFEB was trapped to a similar extent with both forms of muHTT, while TFE3 trapping was significantly increased only with the more aggregation-prone form. In these cells, muHTT also reduced cell viability, with the more aggregation-prone form causing greater toxicity than the shorter form.

Experiments in other lab-grown mouse nerve cells showed that increasing TFEB or TFE3 levels boosted clearance of muHTT and associated clumps, while lowering either protein led to increased accumulation of muHTT.

Only TFEB suppression “significantly worsened muHTT aggregation,” the team wrote, indicating that the two proteins play related, but not identical, roles in controlling muHTT buildup.

Cells producing the more aggregation-prone form of muHTT also showed increased activity of genes encoding proteins involved in LQC and the autophagy-lysosomal pathway, including the gene encoding for LGALS3.

The results suggest “the activation of a cellular response aimed at boosting autophagic clearance of muHTT and to activate LQC to preserve lysosomal integrity,” the researchers wrote.

Based on these results, the team assessed lysosome integrity using LGALS3 as a marker. In cells producing muHTT, LGALS3, which normally appears spread throughout cells, accumulated at the surface of damaged lysosomes, “suggesting that the presence of muHTT concurs to [lysosomal membrane damage] and the impairment of LQC,” the researchers wrote.

Increasing TFEB levels reduced LGALS3 accumulation, suggesting less lysosomal damage, in cells producing either form of muHTT. Increasing TFE3 levels only reduced lysosomal damage in cells producing the more aggregation-prone form of the muHTT, suggesting its protective effect is linked to more severe protein clumping.

“Interestingly, muHTT did not fully co-localize with LGALS3,” the team wrote. That suggests lysosomal membrane damage “is not directly caused by protein aggregates entrapped into lysosomes, but rather that the accumulation of damaged lysosomes might be caused by the depletion of TFEB and TFE3 in [muHTT] aggregates.”

The results “suggest that both TFEB and TFE3 are implicated in [Huntington’s disease], and their sequestration in muHTT [clumps] increase the vulnerability of [nerve cells] to lysosome injury, altering LQC and contributing to disease [development],” the researchers concluded.