Brain Receptor Caught in Action May Help Researchers Find New Huntington’s Treatments

Written by |

A snapshot of a key brain receptor in action might advance the understanding of disease processes in Huntington’s disease and allow scientists to identify new treatments, researchers at Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC) hope.

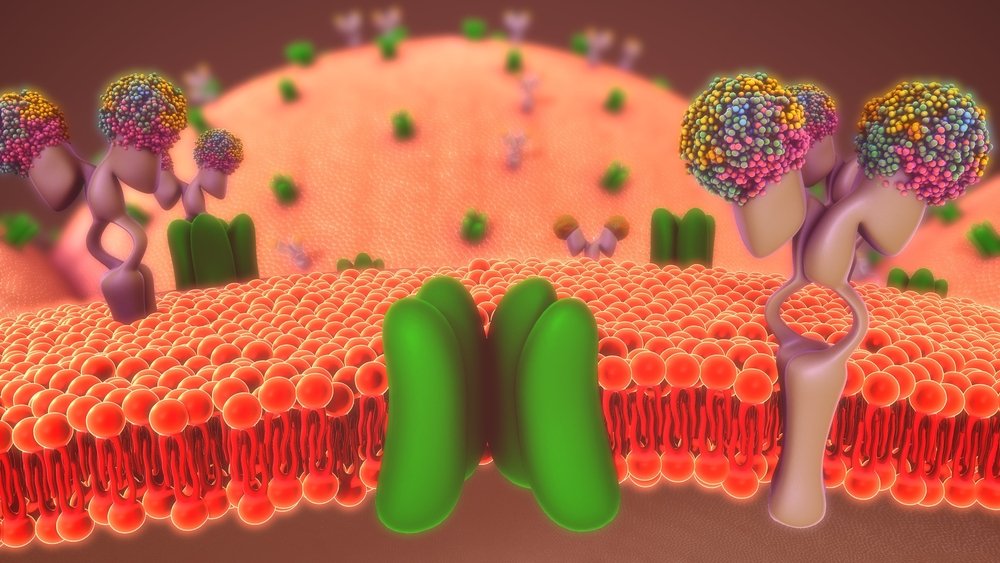

Their work, published in the journal Nature, describes how the neurotransmitter glutamate binds to one of its receptors, called AMPA, in a three-dimensional view.

Glutamate is the most common signaling molecule in the brain, and is crucial for activities such as thinking, learning, and memory.

“With our new findings, we can now, for the first time, visualize how the neurotransmitter glutamate opens glutamate receptor ion channels,” Alexander Sobolevsky, PhD, associate professor of biochemistry and molecular biophysics at Columbia and the senior author of the study, said in a press release.

Titled “Channel opening and gating mechanism in AMPA-subtype glutamate receptors,” the study is yet another advance in the research of this important receptor. The team had previously pictured the receptor alone or together with other factors that control the speed and strength of synapses — the connections between neurons.

To get this snapshot of the receptor, the team used what is known as cryo-electron microscopy. The method, which employs a very high-resolution microscope, captures a large number of two-dimensional images from different angles. These are then combined in the computer to form a 3D image.

But the team also had to freeze AMPA in an active state to allow for the imaging. AMPA is a protein that acts like a pore to allow ions through. These processes, are, however, extremely rapid as the receptor is involved in fast brain processes. A receptor can open and close in less than a millisecond.

Researchers connected the AMPA receptor to another protein that forced the channel open.

Their images show that when glutamate is present, the pore opens up and widens its diameter to let the positively charged ions through. A special lining inside the pore channel aids the ions on their way into the cell.

“These new fundamental discoveries have implications for our understanding of neurotransmission by glutamate, our brain’s major neurotransmitter,” said Edward C. Twomey, a PhD candidate at CUMC and first author of the paper.

“Understanding these processes will impact future studies on glutamate receptor signaling in neurodegenerative diseases as well as drug design,” Twomey said.

These types of molecular insights are crucial when designing drugs that target a specific receptor, such as AMPA.

But Huntington’s disease researchers are by no means the only ones to benefit from these findings. Since glutamate signaling is so important in the brain, other neurodegenerative conditions — and also acute issues such as brain trauma or psychiatric diseases such as schizophrenia or depression — are also influenced by AMPA signaling.

“This is the fundamental process that directly affects learning and memory, and finding its structural determinants has been the primary goal of molecular neuroscience since the ’90s,” Sobolevsky said.