Researchers Identify a Key Link Between the Brain’s Immune Cells and Neurodegenerative Disorders

Researchers at the University of California and the Salk Institute for Biological Studies have identified the mechanisms that make the brain’s immune cells different from all other immune cells

A finding with implications for Huntington’s disease was that genes associated with neurological illnesses have higher lessons of expression in microglia, or the brain’s immune cells, than in other brain cells. Expression is the process by which a gene creates a functional product such as a protein.

The results could help scientists uncover the role microglia play in several neurodegenerative and psychiatric conditions, including Huntington’s, Parkinson’s disease, schizophrenia, autism and depression.

The study, “An environment-dependent transcriptional network specifies human microglia identity,” was published in the scientific journal Science.

“These studies represent the first systematic effort to molecularly decode microglia,” Christopher Glass, a UC San Diego professor who was the senior author of the study, said in a press release. “Our findings provide the foundations for understanding the underlying mechanisms that determine beneficial or pathological functions of these cells.”

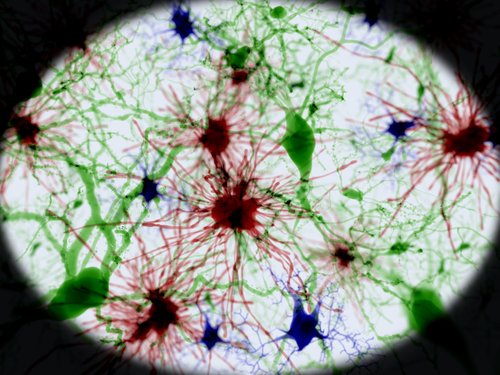

Microglia are responsible for maintaining the brain’s cell balance, which protects it from harmful invaders. They release pro- and anti-inflammatory signals in response to changes in the brain’s microenvironment, and ensure the health of the brain’s neuron network.

The researchers analyzed microglia cells in tissue samples from 19 people who had brain surgery for epilepsy, brain tumor, or stroke. They also looked at microglia cells in tissue from mice.

They found hundreds of genes more highly expressed in microglia than in other immune cells. They also discovered that the genes involved in microglia expression were different from those in other brain cells. And moving cells from tissue to a petri dish culture led to gene pattern changes, they learned.

They concluded that microglia cells have a unique gene expression pattern that changes when the environmental changes. The adjustment was fast, they added. Within just six hours the level of expression in 1,957 genes had increased fourfold, and in more than 2000 genes it had dropped fourfold.

The researchers wondered if the genes that were highly expressed in microglia were associated with neurodegenerative or behavioral disorders, and if their surroundings impacted the level of expression. They found 146 human genes that were associated with neurodegenerative and psychiatric diseases whose expression depended on the surroundings.

But the gene expression in mice tissue differed from that in humans. This suggested that mice may be an unsuitable experimental model for some of these illnesses.

“A really high proportion of genes linked to multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s and schizophrenia are much more highly expressed in microglia than the rest of the brain,” said Nicole Coufal, a pediatric critical care doctor at UC San Diego and a researcher at the Salk Institute. “That suggests there’s some kind of link between microglia and the diseases.”

More studies are required for a better understanding of microglia’s role in the development of neurological and psychiatric diseases, the team said.